Click is a modular router toolkit written mainly in C++, which can be run in both user space and OS kernel space. Since its invention in late 1990s by Eddie Kohler, Click is has gained great successes in both research and industry. This series of notes aims to (1)introduce Click platform, (2)analyze the implementation of Click, and (3) discuss some general problems related to Operating System and Network Programming. The Click Source code can be found here.

Router Models

Click was developed based on an abstract router model. Routers are viewed as pure packet processors: packets arrive on one network interface, travel through the packet processor’s forwarding path, and are emitted on another network interface. In routers, packets flow through the forwarding paths, which behave just like the pipelines. Packets will lose their identity after they arrive the target - only data will be transferred to applications(running on host). One significant differences between routers and hosts is: in packet processors, packets move horizontally between peers, not vertically between application layers.

Click also used an important observation - the packet operation is be basis of computer networks. Firewall limits access to a protected network, often by dropping inappropriate packets. Network address translators allow a large set of machines to share a single public IP address; they work by rewriting packet headers, and occasionally some data. Load balancers send packets to one of a set of servers, dynamically choosing a server based on load or some application characteristic. Therefore, most Click elements center on packet operations.

Click Architecture

The Click architecture is centered on the element. Each element is a software component representing a unit of router processing, which generally examines or modifies packets in some way. At run time, elements pass packets to one another over links called connections. Each connection represents a possible path for packet transfer. A router configuration is a directed graph with elements at the vertices and connections as the edges. Router configurations, run in the context of some driver, either at user level or in the Linux kernel.

A Click router is assembled from packet processing modules called elements. Individual elements implement simple router functions like packet classification, queueing, scheduling, and interfacing with network devices. Configurations are written in a declarative language that supports user-defined abstractions. Due to Click’s architecture and language, Click router configurations are modular and easy to extend. To build a router configuration, Click users can choose a collection of elements and connects them into a directed graph.

In addition to the modular router, Click also supports a configuration scripting language and provides an interpreter, which are also written in C++. Click supports multiple processros and has a builtin scheduler for tasks(elements). These topics will be covered in the future posts.

Elements

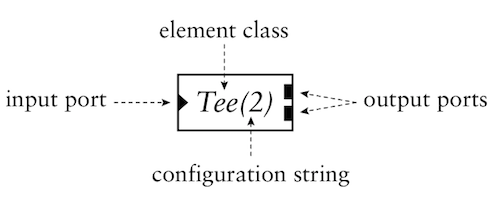

Elements have five important properties: element class, ports, configuration strings, method interfaces and handlers.

- Element class. An element’s class specifies that element’s data layout and behavior.

- Ports. Each element can have any number of input and output ports. Every connection links an output port on one element to an input port on another. Ports may be push, pull, or agnostic.

- Configuration string. optional, contains additional arguments passed to the element at router initialization time. Lexically, a configuration string is a list of arguments separated by commas, i.e.

c1 :: Classifier(9/17, 9/6, -);. - Method interfaces. Each element exports methods that other elements may access. This set of methods is grouped into method interfaces.

- Handlers. Handlers are methods that are exported to the user, rather than to other elements in the router configuration. They support text-based read/write semantics, as opposed to fully general method call semantics. In the Linux kernel driver, handlers appear as files in the dynamic

/procfile system.

An example of real Click element is:

#ifndef CLICK_SWITCH_HH

#define CLICK_SWITCH_HH

#include <click/element.hh>

CLICK_DECLS

class Switch : public Element { public:

Switch() CLICK_COLD;

const char *class_name() const { return "Switch"; }

const char *port_count() const { return "1/-"; }

const char *processing() const { return PUSH; }

void add_handlers() CLICK_COLD;

int configure(Vector<String> &, ErrorHandler *) CLICK_COLD;

bool can_live_reconfigure() const { return true; }

void push(int, Packet *);

int llrpc(unsigned, void *);

private:

int _output;

static String read_param(Element *, void *) CLICK_COLD;

static int write_param(const String &, Element *, void *, ErrorHandler *) CLICK_COLD;

};

CLICK_ENDDECLS

#endif

In above code, the Click macros are defined as:

/* Define macros that surround Click declarations. */

#define CLICK_DECLS namespace Click {

#define CLICK_ENDDECLS }

/* Define macro for cold (rarely used) functions. */

#if __GNUC__ < 4 || (__GNUC__ == 4 && __GNUC_MINOR__ < 3)

# define CLICK_COLD /* nothing */

#else

# define CLICK_COLD __attribute__((cold))

#endif

Where the GNU cold attribute on functions is used to inform the compiler that the function is unlikely to be executed. The function is optimized for size rather than speed and on many targets it is placed into a special subsection of the text section so all cold functions appear close together, improving code locality of non-cold parts of program.

And the handlers of this element can be defined as:

String

Switch::read_param(Element *e, void *)

{

Switch *sw = (Switch *)e;

return String(sw->_output);

}

int

Switch::write_param(const String &s, Element *e, void *, ErrorHandler *errh)

{

Switch *sw = (Switch *)e;

int sw_output;

if (!IntArg().parse(s, sw_output))

return errh->error("Switch output must be integer");

if (sw_output >= sw->noutputs())

sw_output = -1;

sw->_output = sw_output;

return 0;

}

void

Switch::add_handlers()

{

add_read_handler("switch", read_param, 0);

add_write_handler("switch", write_param, 0, Handler::h_nonexclusive);

add_read_handler("config", read_param, 0);

set_handler_flags("config", 0, Handler::CALM);

}

By adding handlers to element Switch, the Switch attributes switch and config can be read or changed by reading/writing files /proc/click/<switch_obj>/switch and /proc/click/<switch_obj>/config at run time, if Click is running in Linux kernel.

Packets

A Click Packet consists of a small packet header and the actual packet data – the packet header points to the data. In the Linux kernel driver, Click packet objects are equivalent to sk_buffs, which avoids translation or indirection overhead when communicating with device drivers or the kernel itself.

Several packet headers may share the same packet data. When copying a packet, Click produces a new packet header that shares the original data. Shared packet data is copy-on-write. Elements that modify packet data first ensure that it is unshared; if it is shared, the element will make a unique copy of the data and change the packet header to point to that copy. Packet headers are never shared, so header modifications never cause a copy.

Headers contain a number of annotations in addition to a pointer to the packet data. Some annotations contain information independent of the packet data - for example, the time when the packet arrived. Other annotations cache information about the data, i.e, the CheckIPHeader element sets the IP header annotation on passing IP packets.

In Linux, the sk_buff is defined as:

struct sk_buff {

/* These two members must be first. */

struct sk_buff *next;

struct sk_buff *prev;

…...

ktime_t tstamp;

struct sock *sk;

struct net_device *dev;

/*

* This is the control buffer. It is free to use for every

* layer. Please put your private variables there. If you

* want to keep them across layers you have to do a skb_clone()

* first. This is owned by whoever has the skb queued ATM.

*/

#ifdef __LP64__

char cb[96] __aligned(8);

#else

char cb[80] __aligned(8);

#endif

unsigned long _skb_refdst;

#ifdef CONFIG_XFRM

struct sec_path *sp;

#endif

unsigned int len,

data_len;

__u16 mac_len,

hdr_len;

union {

__wsum csum;

struct {

__u16 csum_start;

__u16 csum_offset;

};

};

__u32 priority;

kmemcheck_bitfield_begin(flags1);

__u8 local_df:1,

cloned:1,

ip_summed:2,

nohdr:1,

nfctinfo:3;

__u8 pkt_type:3,

fclone:2,

ipvs_property:1,

peeked:1,

nf_trace:1;

kmemcheck_bitfield_end(flags1);

__be16 protocol;

void (*destructor)(struct sk_buff *skb);

……..

int skb_iif;

__u32 rxhash;

__u16 vlan_tci;

……..

sk_buff_data_t transport_header;

sk_buff_data_t network_header;

sk_buff_data_t mac_header;

/* These elements must be at the end, see alloc_skb() for details. */

sk_buff_data_t tail;

sk_buff_data_t end;

unsigned char *head,

*data;

unsigned int truesize;

atomic_t users;

};

The Click Packet is defined as:

class Packet {

…...

private:

// Anno must fit in sk_buff's char cb[48].

/** @cond never */

union Anno {

char c[anno_size];

uint8_t u8[anno_size];

uint16_t u16[anno_size / 2];

uint32_t u32[anno_size / 4];

#if HAVE_INT64_TYPES

uint64_t u64[anno_size / 8];

#endif

// allocations: see packet_anno.hh

};

#if !CLICK_LINUXMODULE

// All packet annotations are stored in AllAnno so that

// clear_annotations(true) can memset() the structure to zero.

struct AllAnno {

Anno cb;

unsigned char *mac;

unsigned char *nh;

unsigned char *h;

PacketType pkt_type;

Timestamp timestamp;

Packet *next;

Packet *prev;

AllAnno()

: timestamp(Timestamp::uninitialized_t()) {

}

};

#endif

/** @endcond never */

#if !CLICK_LINUXMODULE

// User-space and BSD kernel module implementations.

atomic_uint32_t _use_count;

Packet *_data_packet;

/* mimic Linux sk_buff */

unsigned char *_head; /* start of allocated buffer */

unsigned char *_data; /* where the packet starts */

unsigned char *_tail; /* one beyond end of packet */

unsigned char *_end; /* one beyond end of allocated buffer */

# if CLICK_BSDMODULE

struct mbuf *_m;

# endif

AllAnno _aa;

…...

}

Obviously, both Linux sk_buff and Click Packet class have similiar elements, like hearder, data and tail of a packet.

Connections

Each Click connection represents a possible path for packet transfer between elements. Connections are represented as pointers to element objects, and passing a packet along a connection is implemented by a single virtual function call(push or pull). Each connection links a source port to a destination port. The source port is always an output port, and the destination port is always an input port.

Connections link ports, but not elements. Each element may have many ports. If a path exists from an output port o to an input port i in the port graph representation of a router configuration, then we say that i is downstream of o, and conversely, that o is upstream of i.

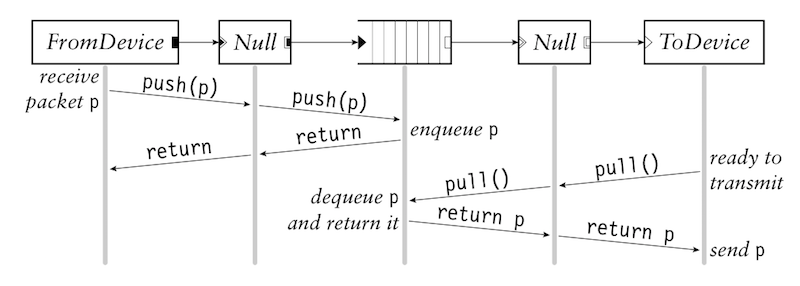

Click supports two kinds of connections, push and pull. On a push connection, packets start at the source element and are passed downstream to the destination element. On a pull connection, in contrast, the destination element initiates packet transfer: it asks the source element to return a packet, or a null pointer if no packet is available. These packet transfers are implemented by two virtual function calls, push and pull.

Connections between two push ports are push, and connections between two pull ports are pull. Connections between a push port and a pull port are illegal. For agnostic ports, they behave as push when connected to push ports and pull when connected to pull ports(Null elements in above picture). In the above picture, Queue element has a push input port and a pull output port - the input port respond to pushed packets by enqueueing them, and the output port responds to pull requests by dequeuing packets and returning them.